Loyalist City Coin in uptown Saint John is a great place to find regional materials long out of print, and last week I spent over an hour flipping through their document bins, pulling out whatever I thought might be of interest to friends and family. For myself, I was delighted to find Joleen Gordon’s book on Edith Clayton’s market baskets, which I hoarded from the UNB library for most of the duration of my PhD, perennially hoping for the time and opportunity to write something about splintwood basketry as an important literary tradition in Nova Scotia.

This poem, written on birch bark and dated August 7, 1900, also stood out to me.

1900 Aug. 7 “Camp Nature” Nerepis N.B.

We sit and look each other at

And feel that we could fly

Because we’re content and all that

Just having done blueberry pieMrs. McKenzie kind and good

Some luscious pies did make

And sent to “Camp Nature” in wood

One that just simply took the cakeAs long as Mrs. Mack’s on earth

May she be blest with all that’s good

‘Tis wished of Pies there’ll ne’er be dearth

By those in “Camp Nature” in wood.“Argole”

Provincial, county, university, and museum archives remain closed at this time, and so the amount of digging I’ve been able to do into the various contexts for this document remains limited. Perhaps unsurprisingly, my Google search for “McKenzie+Nerepis+Pie” was fruitless.

In an essay from The Creative City of Saint John, Donald McAlpine describes Camp Nature as a “summer retreat” on the Nerepis River that “was built between 1899 and 1902 by William McIntosh and Gordon Leavitt on property owned by McIntosh. The camp was the site of Natural History Society of New Brunswick outings, and both McIntosh and Leavitt pursued entomological activity in the surrounding area, Leavitt collecting species of sawflies new to science” (38). We know that Settlers in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries sometimes wrote on birch bark: in 1862, for example, Alex Monro prepared the table of contents for his Native Woods of New Brunswick: – 76 Specimens on bark; and in the 1940s, some soldiers wrote letters home on bark, generally making use of whatever materials were available to them.

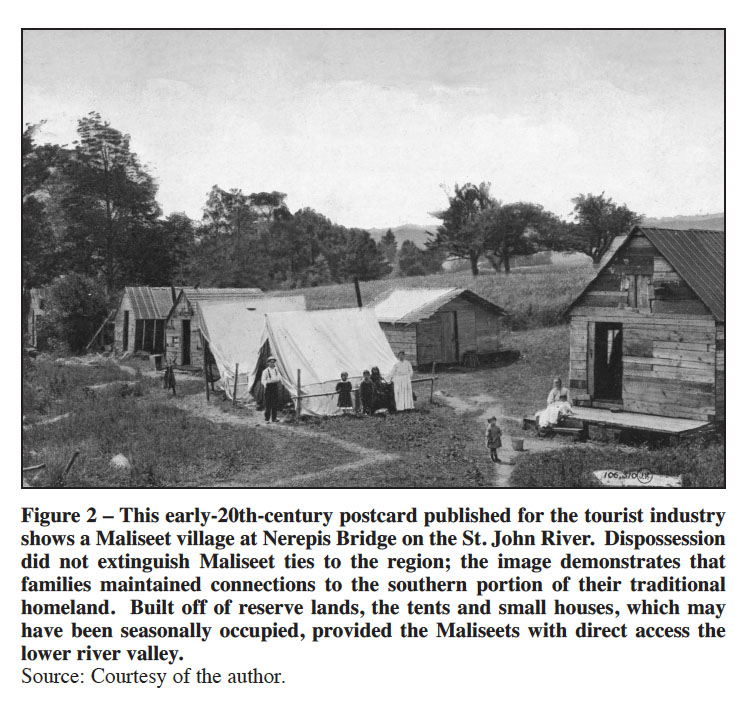

If it is likely, then, that the date of 1900 on the poem is accurate, and that it was written by someone either summering or visiting at Camp Nature in Nerepis, then other Nerepis (or Nalihpick/N’welihpick, meaning “the place where I eat well”) contexts may be relevant. Micah Pawling has written about seasonal camps throughout the Wolastoqey homeland, and he cites the camp at at the confluence of the Nerepis and Wolastoq rivers as one of many instances in which, after the establishment of reserve lands, Wolastoqi people maintained connections with the southern river valley.

Waterscapes and Continuity within the Lower St. John River Valley, 1784-1900,” Acadiensis 46.2 (2017) Link

Anne Sacobie, who lived at St. Mary’s, is but one person who is said to have returned to the camp at Nerepis, along with other camps throughout the southern Wolastoqey homeland, for many years. The following image of her at Evandale is featured on an historical display midway across the Nerepis bridge, which I drove out to examine shortly after finding the poem:

The Wolastoqey camp at Nerepis was active until the 1970’s. Its inhabitants would harvest fiddleheads, ash, and sweetgrass, trap muskrat, fish, and sell or trade materials with other local residents. I do not yet know to what degree the populations from Camp Nature and the Wolastoqey camp might have socialized, but it would not surprise me to learn that the inhabitants of the former benefited — in terms of both materials and information — from the proximity of the latter. At this point in my inquiry, all I can do is speculate, which is not especially useful.

When I first saw this poem in the bin, I immediately intellectually placed it in the tradition of awikhiganak, the writings on birch bark that predate European literary systems in this land. For the Wolastoqiyik, awikhigan had many uses, but one was to communicate survival information, including information about where to find food. I love this poem — about how to stave off blueberry pie scarcity — as an awikhigan, and I am pondering the degree to which this context remains intact and relevant whether it was penned by a Wolastoqi person or not.

Because there is a possibility, however small, that this poem was written by a Wolastoqi person, I am sharing this information early in the research process. It feels ethically ambiguous to keep it to myself, and certainly, if there is any chance that this is a piece of Wolastoqiyik material culture, then I would like to return it to a citizen of that nation as soon as possible. Please e-mail me at rbryant@dal.ca (or send me a message wherever we may be connected) if you have any thoughts or concerns about this aspect of the project.

If, as I currently suspect, the poem was written by a Settler, I am interested to pursue the questions of how Settler and Indigenous communities related to each other in Nerepis at the turn of the 20th century, and in what spirit Settlers in this region, including Monro and others, have participated in the tradition of awikhiganak.

Update: Shortly after publishing this note, I was grateful to hear from Peter Larocque at the New Brunswick Museum: “Just saw your research note regarding Camp Nature. I am not completely certain, but almost convinced that the author, Argole, is one of Camp Nature’s founders, Arthur Gordon Leavitt. ARGOLE is most likely an acronym using the first two letters of each of his names.”