At the beginning of October, Gina and I joined Jessica DeWitt on Instagram Live to help launch the sixth season of NiCHE Conversations. We spoke about the basket restoration that we wrote about back in June [link], and the conversation has now been uploaded to YouTube:

NiCHE — “the stories come alive in it”: Renewing lakotowakən in the Waponahki homelands

Gina Brooks and I were invited to pull a short piece together for the Network in Canadian History & Environment after the inaugural Material Culture Collective gathering at Dalhousie University a few weeks ago. Thanks to Sara Spike for the invite to share.

“With this restoration, Gina wanted to renew a memory of this land as it was back then, a land that could hold caribou. She told Rachel that although Wolastokuk no longer holds caribou, it continues to hold caribou food – these common lichens that remain sensitive to air quality, including twenty-first-century pollution. In this sense, she explained, the land is lonely for the caribou and longs for their return.” [link]

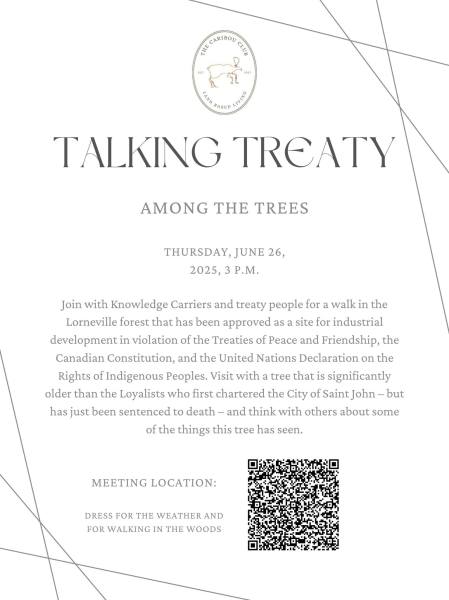

Talking Treaty among the Trees

On Thursday, June 26, Caribou Club organized a walk for treaty people through an old growth forest in Menahkwesk that has recently been rezoned for heavy industry by the City of Saint John without any consultation with Wolastoqiyik. The walk was covered by CBC NB, and the story was also broadcast across the province on Information Morning (audio below).

oetjgoa’tigemg by Tara Francis

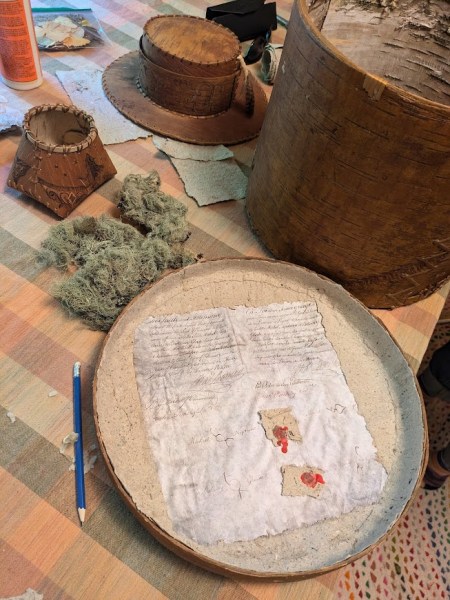

In 2024, I collaborated with Elders Ramona Nicholas and Gina Brooks in support of new work by the brilliant Mi’kmaq porcupine quill artist Tara Francis. This new work from Tara — titled oetjgoa’tigemg, meaning the time that has passed up until now — was reported on in the UNB Newsroom in an excellent story by Kayla Cormier, which you can read in its entirety at this link. Thanks to the Faculty of Arts at UNB in Saint John for commissioning this project.

“Dr. Rachel Bryant, in collaboration with Elder Ramona Nicholas, sourced the historical documents about the Menahkwesk harbour for this commission. She spoke about the importance of Tara’s piece for bringing this history back into our collective consciousness.

‘Here in Saint John, we often think we’ve totally paved over and replaced all that history… We forget the island. We forget the village. We forget the whales. We forget the turtles.’

Despite being embedded in French and Scottish colonial documents, there are stories to be told about this island.

‘Tara’s piece shares this Wabanaki story,’ said Dr. Bryant. ‘I have stories in these documents too—that’s the colonial part.’

She credits Elder Ramona’s scholarship for helping her conceptualize the idea that, in every historical document from this territory, there is a boundary between non-Indigenous and Indigenous Peoples.

‘I am grateful to be able to help pull this information out from these violent contexts and to work with artists like Tara, who can then tell this story in a way that’s beautiful… and removed from those colonial contexts. Now this history is accessible to Wabanaki students in a way that’s not going to hurt them,’ she said.

‘It’s important for Indigenous students to see reflections of themselves and their ancestors on campus. And for settlers to always remember whose land this is and how we got here. To feel connection to these histories and to one another.’

New article: “On Treaty, Virtue, and Plots that Choose Death: Moses Perley’s Sporting Sketches”

I had another article published in the Journal of New Brunswick Studies last week in an issue also honouring Bill Parenteau and Elizabeth Mancke and their many contributions to the field of New Brunswick Studies. My article begins with a section that thinks about Perley in the context of Bill’s work — and when I re-read this piece last week, I could remember the moments that Elizabeth and I argued about along with the parts where she nodded along.

After Elizabeth passed last fall, her Toyota was sold to a brilliant Wolastoqey scholar/educator who is also a dear friend. There was an old, worn out blanket inside, so my talented friend mended it and gave it to me as a gift just a few weeks ago. I keep it draped over my office chair now so I can wrap it around my shoulders when I need to.

And things go on. I revisited and published this article as part of my prep for a class I’m creating for next year on “reading through treaty.” How do settler writers, like Perley but also contemporary writers, create and normalize worlds that exist in contravention of the Peace and Friendship Treaties? How can reading these texts with an awareness of power draw students into the urgent work of restoring our treaty order?

With deep gratitude for my teachers.

“Storytelling is a fight for the future… [and] it is up to us to write a story worth living.” — Kelly Hayes, “Remaking the World”

New article: “wikhikhotuwok and the Re-Storying of Menahkwesk: Telling History Through Treaty”

Gina Brooks and I were honoured to contribute an article to a recent issue of the Journal of New Brunswick Studies commemorating the 25th anniversary of the Supreme Court of Canada’s Marshall decisions. The full text of our contribution (as well as the entire text of this voluminous issue) is online at the following link: https://journals.lib.unb.ca/index.php/JNBS/issue/view/2389

We offer this basket to you in the tradition of Donald Marshall Jr. and in deep gratitude for the great deed he did for the people. Twenty-five years ago, the Supreme Court’s Marshall decision did not create or change the law of treaty in this beautiful land but rather sought to remember it. We invite you to hold this basket in your hands and see what you can remember.

Embracing Ends

Through the years I’ve been fortunate to be a part of intellectual communities and spaces where I have been safe to share my thoughts and ideas freely. I’ve had experienced intellectual mentors who have taught me what this safety was with them, and then, with others. I’m always learning about the importance of having understanding and agreement around clear, shared goals. It’s hard to explain what happens in a space where everyone benefits from the ideas of everyone else over an extended period – where there is no hesitation to share and to give where and when you can, keeping the goal(s) at the centre while also experiencing that magical way in which your own ideas come back to you clearer and stronger with the support of these people who are creating and thinking and feeling with you. When the focus is on a goal, interpersonal conflict and misunderstanding can be worked out – and so these are spaces, too, where people can sometimes disagree, express strong emotion, anger or hurt, hold themselves and one another accountable to the standards and values that give a common goal integrity, make mistakes, forgive and be forgiven. These are essential transitional moments in which we hold and share in one another’s growth – they might not be perfect or always pleasant moments, but they are also never forbidden, and they are important parts of processing our experiences and of practicing our humanity with others.

And I have learned that it’s natural and maybe even important for these communities to end. If we understand common goals as being what bring us together, then we understand, too, that not all of our goals will be shared by every individual with whom we work. The best ends, then, are the ones that come after goals have been met or, maybe just as commonly, failures have been realized, when our focus naturally shifts away from the goal that once brought us into intellectual community with one another, and when we leave the table knowing, on at least some level, and even if there is strong emotion involved in the transiton, that we could return in a future season to build and create and think together again. The worst ends leave us, even months or years later, with regret, grief, or bitterness – these involve manipulation or betrayal or interference. I’ve come to understand and appreciate some of this, as I think many of us have, against the backdrop of how utterly pointless and hollow academic work feels when there is no agreement, when you can’t share or create or build with others, when your instincts tell you not to trust or not to give or that maybe you’ve already shared too much and so now you or someone you love might be used or hurt, when, upon reflection, you can’t point to or articulate specific common values, when all you have are the empty buzzwords or maybe just your own words repeated back to you. This is where the language of “community,” of “ethics,” of “accountability,” of “good relationships” is co-opted, neutralized, and used as a tool to get people (often students) to give much more than what is safe for them. This is when academia, as a system, becomes somehow worse and even more sinister than a matter of warm bodies holding jobs and spaces against transformation, and all you can do is step back, work on forgiving and trusting yourself, nurture those connections that help you learn and think and grow, keep doing your work and remember that sense of purpose that you’ve built and learned and earned over time – because that’s yours. And so maybe you build a wall around your work and your family for a time and you keep your head down, you stay focused, stay focused, you stay true to your values and remember your goals. But it’s still hard, and it’s still sad, because we only have one life, each of us, and we could do so much more.

Research notes: A Subway Under the Harbour in Menahkwesk (1886-1889)

On the 28th of March, 1888, the New Brunswick Lieutenant Governor and Legislative Assembly enacted “An Act to Incorporate ‘The Channel Subway Company,'” a corporation comprised by James Holly, Thomas R. Jones, Hurd Peters, Alfred A. Stockton, and Charles D. Jones. This legislation authorized the Saint John company

“to excavate, build, construct and complete a subway or tunnel, or subways or tunnels, under the waters of the Harbour of the City of Saint John in the Province of New Brunswick, from any point or points on the Eastern side of the Harbour, in the City of Saint John, to any point or points on the Western side of said Harbour in said City, called Carleton, of such form and dimensions, and of such materials as the Company may deem suitable for their purpose, and may lay down and conduct a single or double line of passageway for horses, waggons, vehicles, street cars and foot passengers.”

According to the Act, funds for this questionable endeavour were to be raised through the sale of 7,500 shares worth $100 each. Instead, on January 30, 1889, John Sparrow David Thompson (John A. MacDonald’s Minister of Justice at the time) made a case to the Governor General in Council in Ottawa that “public harbours” like the one in Saint John, under section 108 of the British North America Act,

“are vested in the Crown for the use of Canada. The Supreme Court of Canada has decided in Holman vs. Green, S.C.R., vol. 6, p. 707, that the land covered with water in the public harbours of Canada, belong to the Crown for the use of Canada, and not to the Crown for the use of the province in which such land lies. It therefore follows that the Act in question almost exclusively relates to the public property of Canada, and authorizes an interference with that property. This Act may also be considered as infringing on the power of the Parliament of Canada, exclusively to make laws in respect to navigation . . . [I therefore recommend] that this Act be disallowed unless the Lieutenant-Governor of the province is able to assure your Excellency, before the time for disallowance expires, that the Act will be, or has been repealed.”

Later in the same year, Thompson referred to the Channel Subway Company Act during a debate in the House of Commons as the subject of ongoing “communications . . . between the two Governments.”

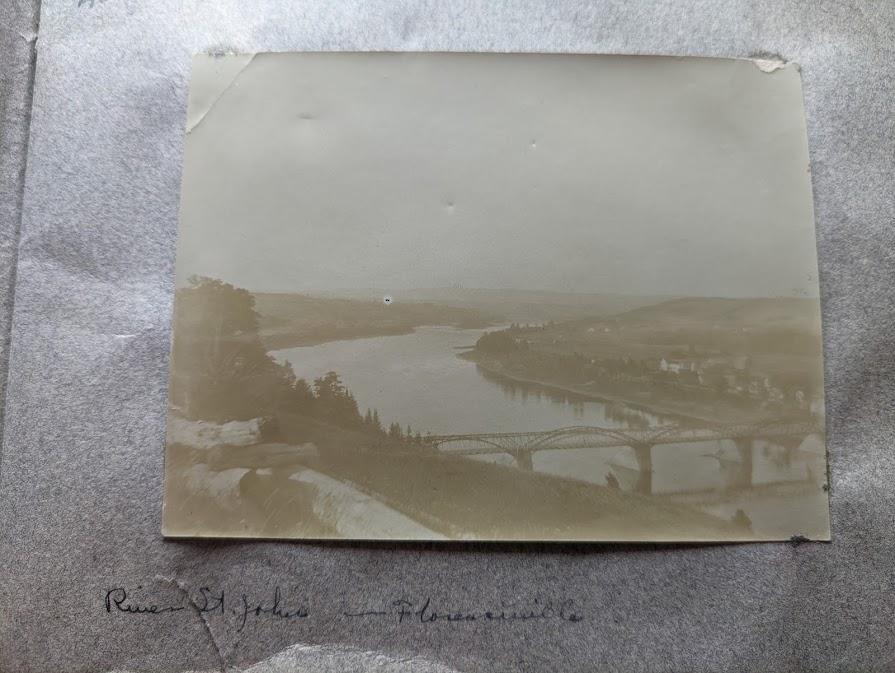

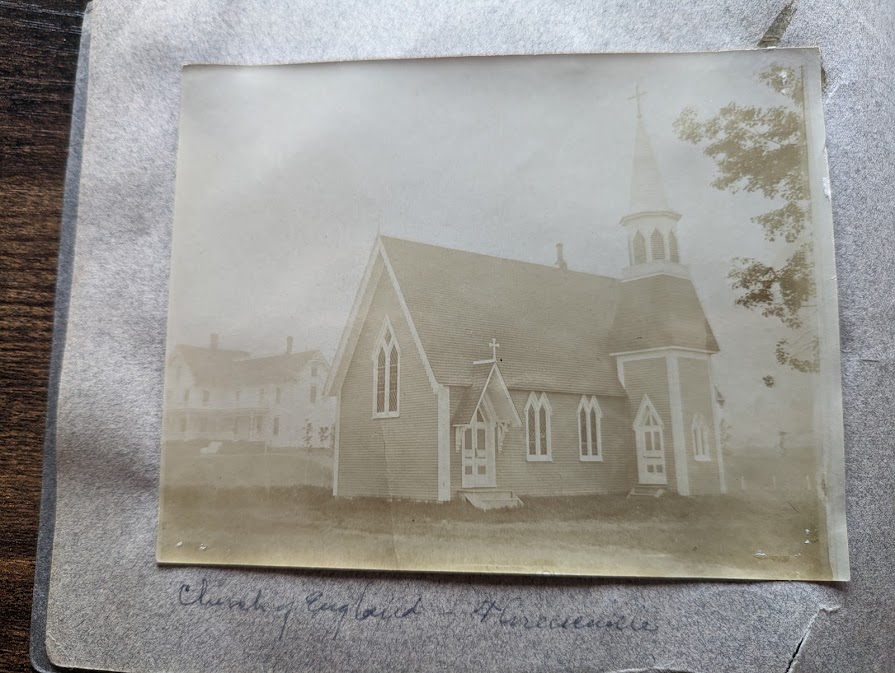

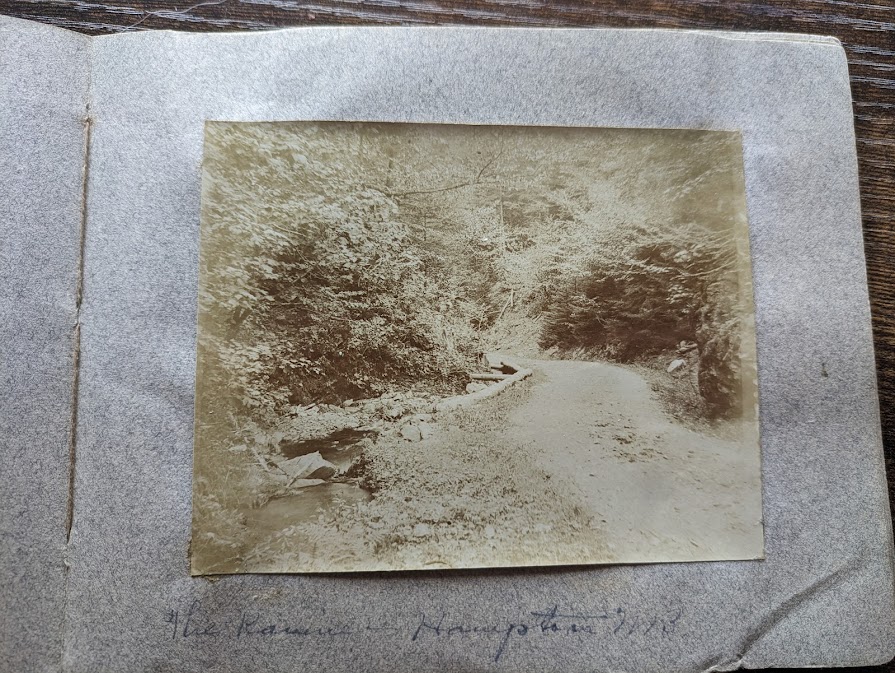

Research Notes: Christmas 1904 Photo Album

An album of photos compiled in 1904 for “Sister Ada with love from Marion.”

(Many thanks to Darlene Partridge, who reached out after seeing this post to share information about Marion Estey [1883-1974] from Wicklow.)

Research Notes: The Wollestook Gazette (1882-1884)

Last week, my search for information about an article published in the Saint John Gazette returned results from the Wollestook Gazette, which I had never heard of. This was a student paper published in Menahkwesk from 1882-1884, and many of their issues can be read online at this link.

In the very first issue, the editors discuss the name of their paper in the following terms:

“The Wollestook Gazette” has not been selected without due deliberation. Our aim as we before stated, is the encouragement of literary tastes and pursuits. We know that the population of St. John has been from very evident reasons largely migratory, consequently we thought that the majority of the inhabitants were ignorant of the Micmac (sic) name of the picturesque river which flows into the magnificent harbour which well nigh surrounds the city. We know that the statement will be contradictory to those of a well-known and fluent historian of this province, but still with youthful hardihood we dare to say that the . . . name of the St. John river was the “Wollestook.” That this is so we think we can prove . . .