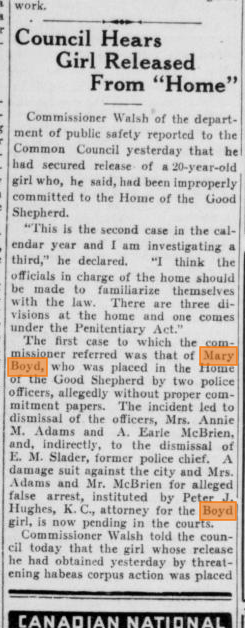

My partner is a criminal defence lawyer and social justice litigator, and when we recently came across this Saint John common council ordinance from 1936 — which authorizes an investigation into the “false arrest of Mary Boyd by City Police” — we were curious about the circumstances and wanted to know more.

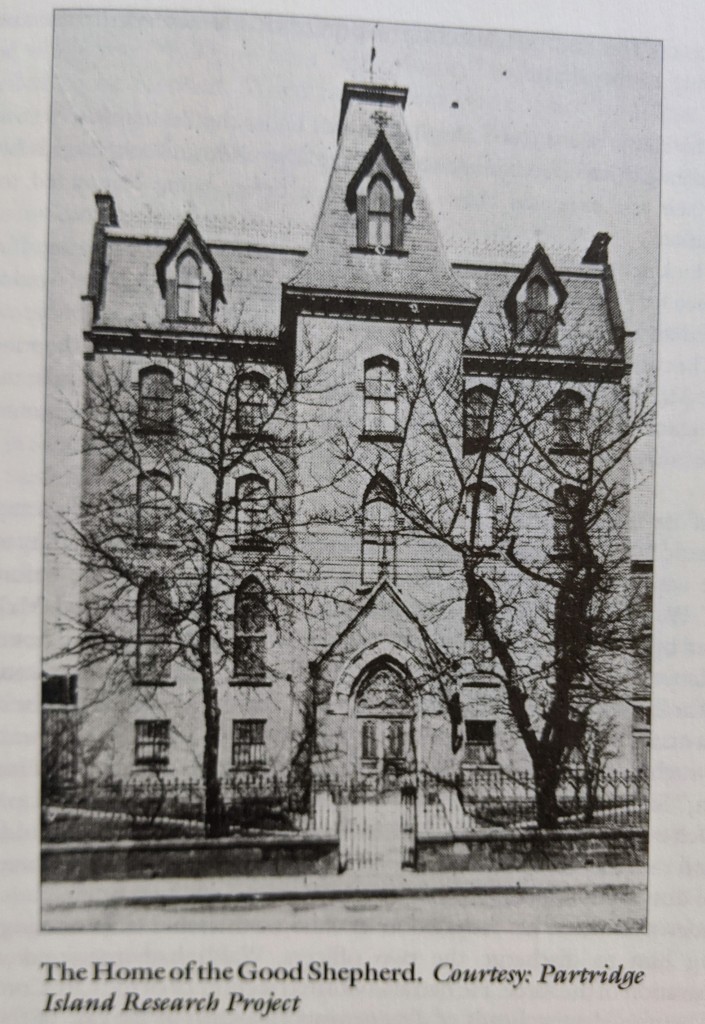

This was a significant political scandal, so there is actually a lot of information about Boyd’s arrest in newspapers from this period. In 1936, she was a seventeen year old girl from Belyea’s Cove who had been arrested and briefly incarcerated, on the recommendation of her aunt, in the House of the Good Shepherd on Waterloo Street in Saint John. The House of the Good Shepherd (also called “Home of the Good Shepherd” and “Good Shepherd Reformatory and Industrial Refuge Laundry”) was one of the many secretive Magdalene laundries that operated in cities throughout North America in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. These institutions were established in Canada in 1844.

We found one image of the building, but after several passes up and down Waterloo Street, we have to assume this was at some point demolished. We have been unable to find a more specific address, but someone with a longer memory of 20th century Saint John might know where this was.

Mary Boyd served three days of a two year “sentence” before her father found out what had happened, traveled to Saint John, and hired a lawyer. The civil suit that the family subsequently filed against the city hinged on several questions, including the legality of actions taken by the arresting officers and whether Mary’s aunt had her father’s approval in seeking Mary’s committal. Edward Walsh’s investigation into this matter, which was authorized by common council on February 6, lead to the termination of Police Matron Annie Adams, Detective A. Earle McBrien, and Police Chief Edward Slader.

In his initial report, Walsh wrote,

The House of the Good Shepherd comes under the Penitentiary Act and no Protestant girl can be committed to the home. Even Roman Catholic girls have to have their case examined before a Magistrate before being committed to this institution.

I look upon the action of these police officers as a very serious matter. If it had not been for Mrs. Alexander Day reporting this case, this innocent girl would have suffered imprisonment for at least two years.

The evidence discloses that these two police officers violated one of the principles of the Magna Charter which we as British people hold very dear; that is, that no citizen can be placed in imprisonment without a proper hearing and being committed by the proper official. (qtd. in Higgins and McGahan, p. 60).

As mentioned above, there is a lot of information available about Mary’s case, including multiple archived court cases and lengthy newspaper articles. But as I read more about this scandal and investigation, what struck me most were not the ins and outs of Mary’s specific case but rather the implications of Walsh’s other findings. In August of 1936, he warned council of a larger, systematic problem, noting that other women and girls were being picked up from the streets of the city and improperly or illegally committed to the House of the Good Shepherd.

We must wonder, then, how many women and girls were improperly detained, and what might have become of those who, once incarcerated, had no people who were able to come for them or no means to hire legal representation or advocacy.

This question is addressed in a new book about these institutions by Rie Croll from the Memorial University Greenfell Campus. In Shaped by Silence: Stories from Inmates of the Good Shepherd Laundries and Reformatories (St. John’s: ISER Books, 2019), Croll interviews women from Ireland, Australia, and Canada whose lives were effectively shaped by their periods of detention in Magdalene laundries. Chapter One tells the story of Chaparral Bowman (nee Georgina Williams) who was born in the House of the Good Shepherd in Saint John to an incarcerated woman named Delcina who may have been Wolastoqi. Chapparal spent the first eighteen years of her life in the institution and sued the Sisters of the Good Shepherd in the 1990’s.

Croll describes the House of the Good Shepherd as “a thriving and lucrative laundry business, so successful that it posed a threat to similar Saint John businesses” (p. 56). Using newspaper records, she cites a long history of public lobbying against the institution that failed to reform exploitative business practices. In 1896, for example, one business owner complained that “‘Any girl could be sent to the convent from any part of the province, either by her father or guardian if he found he could not control her. Then the sisters had the benefit of her labour'” (qtd. in Croll, p. 56). Chapparal maintains that her mother “committed no crime” and yet was detained in the laundry service “until she was no longer able to work.”

Notably, it was requested that the “Reformatory of the Good Shepherd” in Saint John be added to the list of Canadian residential schools recognized by the “Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement.” It is widely accepted that there were no residential schools within the borders of what is currently New Brunswick. The request to add the House of the Good Shepherd was assessed against “Article 12” in the Settlement Agreement and refused on the basis that the institution was provincially, rather than federally, operated.

I met Georgina Williams in 2005 for the first time and again in 2009, a beautiful and amazing woman. She told me she called ‘Delcina’s Tears’ a work of fiction because the judge threw out her case and called her a liar. I just found this blog now as I was thinking of her and was trying to see what happened with this very important story.

Thank you for doing good work and looking into this.

LikeLike

Hi Darryl — Thanks so much for this note and for sharing your impressions of Georgina. I am so glad that this common council ordinance led me to her story. What happened to her (and then what happened to her again in the courts) was unfair. I am working on an article about Delcina’s Tears and will share it here when it is published. Best wishes.

LikeLike

Hi,I am looking for information on my mom to get closure…she was at Good Shepherd. Any help on or information on this place would be welcomed.

LikeLike

Hi Trisha, I’m afraid I don’t have a lot more information than what I’ve shared here. Here is the chapter on the House from Rie Croll: https://atlanticbookstoday.ca/wp-content/uploads/samples/9781894725538.pdf

I added a small amount of additional information here: https://rachelbryant.ca/2021/06/09/additional-information-about-the-house-of-the-good-shepherd/

If you cannot access the Mike Landry piece (it’s behind a paywall), please send me an e-mail and I can send it to you. rachel.bryant@unb.ca

Best wishes.

LikeLike

Thank you,I couldn’t access Mike Landrys article

LikeLike

Hi Trisha, if you’d like to send me an e-mail, I can share the article. rachel.bryant@unb.ca

LikeLike

Thank you for this article about the Home of the Good Shepherd on Waterloo Street. Since the 1931 Census of Canada was released this week, I’ve been searching for a particular family and found one member at this institution. Frances had been born to an unwed mother named Rose, who was one of the British Home Children sent to Canada by Middlemore Home in Birmingham, England. Frances was the third child born to Rose and it looks like the first two may have died.

On the 1921 Census, both Frances and Rose, were at the Municipal Home in Saint John. Four years later, Rose married a man she met at the Municipal Home, but they did not raise Frances together. Frances must have been transferred to the Home of the Good Shepherd around the time her mother got married. Rose died in 1930 after having two more children with her husband. Frances later married and had a daughter, who has enlisted my help in searching for her family roots. We are awaiting DNA results, which should provide more clues.

Your comment about being unable to find the exact location of this institution led me to dig a little deeper. The 1931 Census mentioned that several of the girls at the Home had the address of 133 Waterloo Street. Google Map shows that to be a building on the corner of Waterloo and Golding Streets, probably not the same structure as existed in 1931. Nearby is the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception, St. Joseph’s Hospital, Coverdale Centre for Women and the Outflow Men’s Shelter.

I look forward to learning more about this subject from the links you have shared.

LikeLike